"The V for victory sign is being displayed prominently in all so-called democratic countries, which are fighting for victory... Let we colored Americans adopt the double V for a double victory. The first V for victory over our enemies from without, the second V for victory over our enemies from within." (James G. Thompson, 1942)

In response to the United States entering World War II in 1941, James G. Thompson wrote a letter to the Pittsburgh Courier, a black newspaper, expressing his concerns about discrimination in the war and in general toward African Americans in the US. Thompson was a cafeteria worker in a Kansas aircraft manufacturing plant. He was 26 years old. The idea he proposed in this article was to start a movement for two causes. Not just so Africans could fight and participate in the war, but also in everyday society, as equal citizens.

The story of the campaign and its antecedents is quite fascinating. When the war broke out, the overwhelming number of black soldiers served in segregated units. Rather than tackle integration of the military head-on, civil rights leaders A. Philip Randolph, Walter White and others organized a March on Washington to protest discrimination in the defense industry, which, well before Pearl Harbor, was receiving lucrative contracts from Uncle Sam to build up Britain’s and the nation’s defenses.

Eleanor Roosevelt met with Randolph and White to ask them to call the march off, but they refused; FDR then met with them, but they still refused — unless he signed an executive order banning discrimination in the defense industry. Facing a public relations disaster, FDR came around, and on June 25, 1941, he issued Executive Order 8802, creating the Fair Employment Practices Committee to enforce a new rule — that “there shall be no discrimination in the employment of workers in defense industries or government because of race, creed, color, or national origin.”

The march was called off, but it laid the groundwork for MLK’s March on Washington in 1963. And it established the mood within the black community to monitor race relations at home, even amid the war against fascism abroad. One man, deeply concerned about all of this, sat down and wrote a letter to the most influential black newspaper in the country. On Jan. 31, 1942, the Pittsburgh Courier published a letter to the editor from James G. Thompson of Wichita, Kan. It was titled “Should I Sacrifice to Live ‘Half American?‘ ”

In it, Thompson wrote: “Being an American of dark complexion and some 26 years, these questions flash through my mind: ‘Should I sacrifice my life to live half American?’ ‘Will things be better for the next generation in the peace to follow?’ ‘Would it be demanding too much to demand full citizenship rights in exchange for the sacrificing of my life?’ ‘Is the kind of America I know worth defending?’ ‘Will America be a true and pure democracy after this war?’ ‘Will colored Americans suffer still the indignities that have been heaped upon them in the past?’ These and other questions need answering.”

Then he proposed what he called “the double V V for a double victory … The V for victory sign is being displayed prominently in all so-called democratic countries which are fighting for victory over aggression, slavery, and tyranny. If this V sign means that to those now engaged in this great conflict, then let we colored Americans adopt the double V V for a double victory. The first V for victory over our enemies from without, the second V for victory for our enemies from within. For surely those who perpetuate these ugly prejudices here are seeking to destroy our democratic form of government just as surely as the Axis forces.” [Read Thompson’s full letter to the Courier here.]

The Courier was the most widely read black newspaper during the war, with a national circulation well above 200,000. It had already run stories protesting the Navy’s use of black sailors only as “messmen,” and on Jan. 3, 1942, the paper denounced the American Red Cross’ refusal to accept black blood in donor drives, under the title “The Red Blood Myth.” But nothing could prepare the editors for the enthusiastic response of the public to Thompson’s letter.

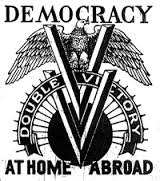

A week later, on Feb. 7, 1942, two months to the day after the Pearl Harbor attack, the Courier published on its front page an insignia announcing “Democracy At Home Abroad.” The following week, the paper announced that it had published the insignia “to test the response and popularity of such a slogan with our readers. The response has been overwhelming.” Henceforth, “this slogan represents the true battle cry of colored America.” As the editors conclude, “we have adopted the Double ‘V’ war cry — victory over our enemies on the battlefields abroad. Thus in our fight for freedom we wage a two-pronged attack against our enslavers at home and those abroad who would enslave us. WE HAVE A STAKE IN THIS FIGHT … WE ARE AMERICANS TOO!” the full editorial online here.

The Double V Campaign ran weekly into 1943. To promote patriotism, the Courier included an American flag with every subscription and encouraged its readers to buy war bonds. Double V clubs spread around the country. Among the campaign’s features, the paper published a weekly photo of a new “Double V Girl” frequently lifting two fingers in a “v” sign; celebrity and political endorsements followed, including Lana Turner (who, in a bit of cross-promotion, mentioned that her movie Slightly Dangerous featured blacks in the cast) and former presidential candidate Wendell Willkie, wearing a Double V pin, which the Courier sold for five cents, as William F. Yurasko reports. A Double V hairstyle called “the Doubler” also became popular, historian Patrick Washburn recalls, as did Double V gardens and Double V baseball games. Other black newspapers soon joined the Courier’s campaign.

To measure the campaign’s impact, the Courier ran a survey. On Oct. 24, 1942, it published the results: In response to the question, “Do You Feel that the Negro Should Soft Pedal His Demands for Complete Freedom and Citizenship and Await the Development of the Educational Process?” 88.7 percent of readers responded no, with only 9.2 percent responding yes.

Needless to say, not everyone was pleased with the Double V Campaign: As Washburn writes in A Question of Sedition, the federal government systematically monitored the black press, including this campaign, during the war. Accordingly, to avoid charges of disloyalty or aiding and abetting the enemy, the Courier’s editorial added a caveat to its poll results: “No one must interpret this … as a plot to impede the war effort. Negroes recognize that the first factor in the survival of this nation is the winning of the war. But they feel integration of Negroes into the whole scheme of things ‘revitalizes’ the U.S. war program.”

Legacy of the Campaign

In September 1945, the Double V insignia disappeared from the paper, replaced in 1946 by a Single V, indicating that more work combating antiblack racism needed to be done at home. But as Clarence Taylor concludes, “Although the Courier could not claim any concrete accomplishments, the Double V campaign helped provide a voice to Americans who wanted to protest racial discrimination and contribute to the war effort.”

While the Courier’s campaign kept the demands of African Americans for equal rights at home front and center during the war abroad, we can also argue that the Double V Campaign had at least two important legacies following the war: First, through the columns of its sportswriter, Wendell Smith, which featured prominently in the film 42, it doggedly fought against segregation in professional sports, contributing without a doubt to the Brooklyn, N.Y., Dodgers’ decision to sign Jackie Robinson in 1947, which in turn had a ripple effect. And on July 26, 1948, President Harry Truman issued Executive Order 9981, which ordered the desegregation of the U.S. armed forces. With that action, the Double V Campaign had at last realized one of its principal goals.

The military service of black men and women before and after the desegregation order, and the strength of the Double V Campaign, helped to inspire the modern civil rights movement that began in earnest just after the war ended. Both efforts remain worthy of remembrance on this Memorial Day holiday.

The killing of two New York City police officers on December 20, 2014, while they sat in their patrol car near a public housing project in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, has riven the city…Almost immediately after the event, it began to seem that a third casualty might be the national protest movement focused on policing and racial injustice that had assumed, in recent weeks, the moral force of a fundamental civil rights issue, attracting widespread political and popular support. With staggering, but predictable, alacrity, some pro-police figures put forth an argument that they believed inescapably linked the protest movements to the murders. Protesters had called for the death of cops, went the argument, and the call had been answered...by a twist of rhetoric, members of a nonviolent civil rights movement who were trying to draw attention to an entrenched pattern of abuse of innocent citizens had become linked to a mentally unbalanced criminal…During the week after the police killings, police virtually ceased writing parking tickets and making arrests; by the second week of the slowdown, there was an increase in serious crime…A lesson from the police killings and their aftermath is how immensely hard it is for black people to get across that the criminal justice system treats them shamefully and as if they were universally dangerous. After the killing of unarmed blacks in Ferguson, New York, and Cleveland these past months, that message has begun to get across—thanks to a multiracial movement led by young blacks. Policing has become a civil rights issue. What mustn’t get lost is the debate about a grand jury system where the conflicts of interest of prosecutors, who work closely with police, make criminal indictment in cases of violent police misconduct almost impossible to obtain. The appointment of special prosecutors in these cases is an obvious solution. A shift toward collaborative policing, where the wishes and desires of community members are taken into account, is, if Bratton and de Blasio are to believed, already underway in New York.

Thank you, President DeGioia. And good morning, ladies and gentlemen. Thank you for inviting me to Georgetown University. Beautiful Healy Hall—part of, and all around where we sit now—was named after this great university’s 29th President, Patrick Francis Healy. Healy was born into slavery, in Georgia, in 1834…With the death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, the death of Eric Garner in Staten Island, the ongoing protests throughout the country, and the assassinations of NYPD Officers Wenjian Liu and Rafael Ramos, we are at a crossroads. As a society, we can choose to live our everyday lives, raising our families and going to work, hoping that someone, somewhere, will do something to ease the tension—to smooth over the conflict. We can roll up our car windows, turn up the radio and drive around these problems, or we can choose to have an open and honest discussion about what our relationship is today—what it should be, what it could be, and what it needs to be—if we took more time to better understand one another…Unfortunately, in places like Ferguson and New York City, and in some communities across this nation, there is a disconnect between police agencies and many citizens—predominantly in communities of color…Serious debates are taking place about how law enforcement personnel relate to the communities they serve, about the appropriate use of force, and about real and perceived biases, both within and outside of law enforcement. These are important debates. Every American should feel free to express an informed opinion—to protest peacefully, to convey frustration and even anger in a constructive way. That’s what makes our democracy great…Let me start by sharing some of my own hard truths: First, all of us in law enforcement must be honest enough to acknowledge that much of our history is not pretty. At many points in American history, law enforcement enforced the status quo, a status quo that was often brutally unfair to disfavored groups…little compares to the experience on our soil of black Americans. That experience should be part of every American’s consciousness, and law enforcement’s role in that experience—including in recent times—must be remembered. It is our cultural inheritance…Many people in our white-majority culture have unconscious racial biases and react differently to a white face than a black face…America isn’t easy. America takes work. Today, February 12, is Abraham Lincoln’s birthday. He spoke at Gettysburg about a “new birth of freedom” because we spent the first four score and seven years of our history with fellow Americans held as slaves—President Healy, his siblings, and his mother among them. We have spent the 150 years since Lincoln spoke making great progress, but along the way treating a whole lot of people of color poorly. And law enforcement was often part of that poor treatment. That’s our inheritance as law enforcement and it is not all in the distant past. We must account for that inheritance. And we—especially those of us who enjoy the privilege that comes with being the majority—must confront the biases that are inescapable parts of the human condition… It is time to start seeing one another for who and what we really are. Peace, security, and understanding are worth the effort. Thank you for listening to me today.

In our collective imaginations, we tend to conceive of the constantly called-for “national conversation on race” as having the formality of some grand conclave of consciousness — an American Truth and Reconciliation equivalent, a spiritual spectacle in which sins are confessed and blame taken and burdens lifted.

This may be ideal, but it is also exceedingly unlikely in this country, particularly in this political environment. There will be no great atoning. Reparations will not be paid. There will no sprawling absolution.

Yet we can still have a productive conversation. Indeed, I would argue that we are in the midst of a national conversation about race at this very moment. Its significance isn’t drawn from structure but from the freedom of its form.

Every discussion over a backyard fence or a cup of coffee is part of that conversation. It is the very continuity of its casualness that bolsters its profundity.

We need to stop calling for the conversation and realize that we are already having it.

Last week the F.B.I. director, James Comey, added his voice to that conversation, particularly as it relates to the relationship between law enforcement and communities of color. There were portions I found particularly potent coming from a man in his position.

He gave a list of “hard truths,” the first of which was an admission that the history of law enforcement in this country was not only part of the architecture of oppression but also a brutal tool of that system. As Comey put it, “One reason we cannot forget our law enforcement legacy is that the people we serve and protect cannot forget it, either.”

His second hard truth acknowledged the existence of unconscious racial bias “in our white-majority culture” and how that influences policing.

Third, he acknowledged that people in law enforcement can develop “different flavors of cynicism” that can be “lazy mental shortcuts,” resulting in more pronounced racial profiling.

But as in all discussions, there were portions of the speech to which I took exception.

First, Comey seems to falsely conflate condemnation of poor policing — sometimes predatory policing, in particular — with a condemnation of all policing. He makes a straw man argument, “Law enforcement is not the root cause of problems in our hardest hit neighborhoods.” Who said it was?

This is a twisting of motive and purpose of the voices of recent protesters that undermines and mischaracterizes both. Minority communities want policing the same as any other, but they want it to be appropriate and proportional. They want not to be afraid of the cops as well as the criminals. They want officers to display an equitable modicum of discernment in treating the law-abiding differently from the lawbreaking.

The discussion is not about police officers being a “root cause of problems” in a given neighborhood, but rather that they shouldn’t be a problem at all, anywhere. We are not geographically confined. We can move in and out of high-crime neighborhoods. We can’t move in and out of our own skin.

At another point, Comey states that cynicism “becomes almost irresistible and maybe even rational by some lights.” This is dangerous and unconditionally false. “Lazy mental shortcuts” — in other words, racial profiling — aren’t rational in any light. That violates not only an American principle but also a human one: that no person should be punished for the crimes or sins of another.

His fourth hard truth focused on how crimes among “many young men of color become part of that officer’s life experience.” But in seeking to offer context, he mentioned “environments lacking role models, adequate education, and decent employment.” Here he moves perilously close to a racial pathology argument, as if there were something inherent in blackness and black culture that predisposes one to criminality. This, too, is a “lazy mental shortcut."

What too few people mention when discussing crime is the degree to which concentrated poverty, hopelessness and despair are the chambermaids of violence and incivility. These factors are developed and maintained through a complicated interplay of structural biases — historical and current — interpersonal biases, environmental reinforcements and personal choices.

Even as I disagree on portions, I take the larger point, and I applaud the endeavor and its purpose. Comey seems to be making a genuine effort to be part of the conversation and the solution, and that is more than I can say for some.

One doesn’t have to possess the certitude of gospel to have a positive impact on this discussion — for oneself and others. Just an earnest desire for insight and mutual understanding.

This is more than one can say of the hard of heart, those resistant to engagement and, therefore, beyond enlightenment. The stone cannot absorb no matter how much you drench it.

© Copyright 2012 The Kemper Human Rights Education Foundation. All rights reserved.