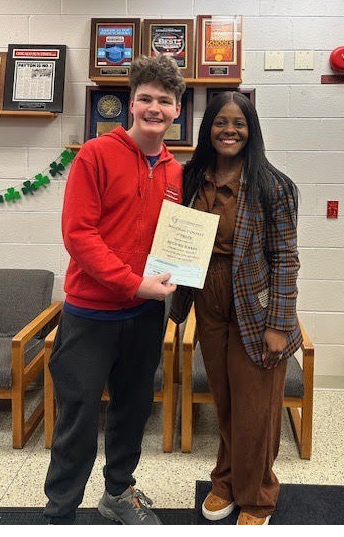

Hugo Richards

Grade 10

Walter Payton College Preparatory School, Chicago, IL

1st Prize

Navigating the Line Between Liberty and Dignity

Hate speech, once confined to the fringes of society, is now more pervasive than ever, seeping into mainstream conversations, political speeches, and our social media feeds. In November 2024, racist and offensive text messages about slave catchers and mass deportations were sent to Black and Latino individuals across the United States. Recipients reported feeling targeted, hurt and unsafe,[1] showing the real-world harm that hate speech causes. While freedom of speech is a cornerstone of democracy, can it cross the line from protected speech to violating human rights like dignity, equality and security?

United Nations (UN) Secretary-General António Guterres considers hate speech a threat to human rights but suppressing it outright risks infringing freedom of speech. These conflicting rights pose a challenge for nations:protecting citizens from the harm of hate speech while preserving free speech. How, then, should hate speech be addressed in a way that navigates the line between upholding dignity (the right to inherent worth and value) and safeguarding liberty (the right to free expression)?

Hate Speech and Human Rights

Hate speech is on the rise.[2] Fueled by the internet, it is increasingly exploited by extremists, cyberbullies and politicians. In today’s globally interconnected world, it impacts every society and culture, yet its lack of a universally accepted definition is one of its greatest challenges. Consistent with the UN, hate speech refers to any form of speech, writing, or behavior that attacks or discriminates against someone based on who they are.[3] More than just provocative or offensive language, it deliberately intends to harm, intimidate and degrade based on immutable characteristics like race, sexual orientation or gender. It promotes hatred and division through excluding and dehumanizing individuals and groups. Rooted in underlying systemic inequalities, it functions as a ‘mechanism of subordination’, designed to reinforce power imbalances and keep marginalized communities oppressed.[4]

As shown with the racist text messages, hate speech inflicts immediate and lasting mental, emotional and physical harm. But it doesn’t only need to target individuals by name to inflict injury. Indirect hate speech, such as broader racist or homophobic rhetoric, creates a climate of fear and exclusion, erodes victims’ dignity and security, and causes long-term psychological distress. Repeated exposure to hate speech has a cumulative, detrimental effect on societies, deepening divisions, silencing marginalized groups and denying them opportunities.[5]

The more hate speech is normalized, the more it risks escalating to violence andhate crime, as seen with events like the Holocaust and 1994 Rwandan genocide. The Anti-Defamation League's ‘Pyramid of Hate’ illustrates how hatefulbiases can escalate from thoughts to violent actions,[6] evident in the 2019 Christchurch and 2022 Colorado mass shootings, where the attackersshared extremist views prior to their attacks.[7]When politicians such asPresident Trump use global platforms to spread divisive rhetoric, like hisanti-Muslim and anti-immigrant comments, it normalizes hate,stokes division and encourages violence against minorities.[8] This was seen in Myanmar in 2017, where anti-Rohingya language fueledtheir later persecution and genocide.[9]

It is clear that hate speech threatens our human rights to live free and equal in dignity and rights, with security of person and without discrimination as enshrined in the UN Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR).[10] By promoting hatred and division, hate speech contradicts the core principle that everyone deserves the right to dignity, equal treatment, equal protection, and freedom from violence and discrimination.

However, suppressing hate speech outright, before it has a chance to be heard, risks infringing another human right: the right to freedom of opinion and expression, as also enshrined in the UDHR (Article 19). This right is protected in other international human rights frameworks like the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (Article 19) and the European Convention on Human Rights (Article 1), and national constitutions like the U.S. First Amendment. Our right to free speech is at the core of democracy, truth and liberty and is crucial for us to exercise other rights, such as voting and assembly,[11]so should it override our other rights when they conflict?

Free-speech advocates say yes,free speech should be prioritized to protect liberty.[12] They argue that society benefits when it permits all ideas, even hateful and shocking ones, into a diverse 'marketplace of ideas' that will naturally allow strong ideas to prevail and weak ones to be rejected. This concept is rooted in John Milton’s centuries-old argument that truth will always triumph in a free and open exchange of ideas,[13] and echoed by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes’ assertion that the truest test of an idea lies in its ability to gain acceptance through open competition.[14]Regulating hate speech, therefore, risks compromising democracy bythreatening liberties, stiflingopen debate, and leadingus down a dangerous path toward censorship and suppression.

However, in today’s digital age, the concept of a functioning marketplace requires re-examination.[15] Online dissemination of hate speech often allows it to grow stronger, not weaker, and spread farther than Milton ever envisioned. Moreover, access to the digital marketplace is uneven, where some voices go unheard, and others are amplified to millions of followers. Even free-speech advocate John Stuart Mill acknowledged that limits on free speech would be necessary if its harm outweighed its benefit.[16]

International Approaches

Despite the fundamental value offree speech, international frameworks like the UDHR (Article 1) and the ICCPR (Article 22.2) have increasingly advocated for hate speech restrictions. Western nations in Europe, along with countries like Canada, Brazil, Israel, India and Australia, have all passed laws restricting hate speech,[17] affirming that freedom of expression may be limited to uphold the human rights of others. Reid (2024) describes this as the ‘dignity approach’, where nations maintain the right to free speech but place it secondary to the right to dignity.

Each country’s legal frameworkfor confronting hate speech reflectsits unique history. For example, Germany bans Nazi symbols to prevent the rise of far-right ideologies, while South Africa’s laws stem from its post-apartheid efforts at reconciliation. Canada enforces strict hate speech laws to protect its multi-ethnic and multi-racial society, and Brazil’s criminalization of hate propaganda derives from its history of slavery.[18] Eleven European countries specifically criminalize Holocaust denial or justification.[19] These examples illustrate that, while these nations differ in their experiences, each nation reinforces its commitment to rights of equal treatment and human dignity over free speech. Social philosopher Karl Popper advocated that free and open societiesshould maintain the right “not to tolerate the intolerant”, drawing a line between speech that contributes to democratic society, and speech that threatens it.[20]

In contrast, the U.S. follows a ‘liberty approach’ (Reid, 2024) that prioritizes free speech over human dignity, as seen in the Supreme Court’s 1977 decision to defend a neo-Nazi demonstration in Skokie, Illinois.[21] This approach puts the U.S. out of step with almost every other liberal democracy, and ignores large numbers of Americans who support limits on hate speech.[22]But First Amendment protection doesn’t grant the right to say anything you want. Some speech, like defamation and obscenity, is restricted as long as the restriction is content-neutral, meaning it cannot be banned simply for being offensive. Hate speech, therefore, remains protected in the U.S. unless it constitutes a true threator risksimminent harm,[23] a standard that ignores the long-term harm hate speech causes, and disregards international human rights obligations.

Rather than altering First Amendment protections, the U.S. favors ‘counterspeech’ over censorship, advocating for “more speech, not enforced silence”.[24] Peaceful counter-demonstrations, the public outpouring of opposition to the alt-right demonstrations in Charlottesville, Virginia in 2017, and public backlash, like cancel culture, are examples of ways civil society can self-regulate without suppression.[25]Although also endorsed by the UN,[26]counterspeechcan dismiss real-life harm and allow hate speech to continue unchecked. Moreover, counterspeech is not feasible in cases like swastika graffiti, online hate posts, or the anonymous racist text messages previously referenced. Counterspeech, therefore, offers a potential solution, but not a complete one.

Furthermore, the U.S. legal framework faces criticism for failing to fully integrate international human rights treaties like the ICCPR into domestic law,[27] creating legal and cultural gaps in global protections. These gaps have widened with the rise of digital communication, allowing hate speech and extremist ideologies to spread rapidly across borders. While 55% of EU respondents report experiencing online hate speech, the figure rises to 65% in the U.S.[28] With over five billion internet users worldwide,[29] content shared legally in the U.S., such as Holocaust denial, can instantly reach countries where it is criminalized, highlighting the urgent need for consistent international standards and regulations.

Social media amplifies the online spread of hate speech, with platforms like Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), and YouTube profiting from engagement-driven algorithms that prioritize provocative and controversial content. While platforms pledge to remove harmful content, much still slips through. Facebook for example, with three billion monthly users, removed only 38% of flagged hate speech in 2018,[30] and was instrumental in “supercharging” the spread of anti-Rohingya rhetoric in 2017.[31] This enables extremists to push harmful ideologies into the mainstream, reach global audiences, and stoke real-world violence. While the EU requires hate speech removal within twenty-four hours, the U.S., prioritizing First Amendment protections, grants companies broad discretion. As a result, 40% of global hate speech now originates from U.S.-based platforms.[32] Lenient content moderation policies, such as those advocated by Elon Musk for X, have increased online hate speech, misinformation and harassment,[33] with use of the racist “N-word” surging by almost 500% since his acquisition.[34]

In agreement with António Guterres, hate speech poses a significant threat to human rights of dignity, equality and security, exacerbated by the internet’s global reach, social media amplification, and inconsistent legal approachesbetween the U.S. and the international community. Attempts to remove online hate speech are often inadequate and fail to address underlying prejudices. So, how should governments deal with the threat of hate speech in a way that balances dignity and liberty?

Recommendations

Ideally, the U.S. would reconsider its position on the First Amendment to exclude certain forms of hate speech, as it has done with defamation and obscenity, and affirm that hate speech undermines dignity, violates the rights of its targets, and brings no value to the marketplace of ideas. This would also align with the international community in affirming the priority of human rights protections. However, given the strong resistance in the U.S. to amending it,[35] these recommendations focus on content moderation, algorithm regulation, education, and international cooperation.

To counter hate speech’s global spread, governments need to enforce stricter content moderation policies on internet platforms. The U.S. has one of the most permissive regulatory environments, largely due to Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act (1996). This provision shields platforms from liability for user-generated content, letting them adopt a ‘hands-off’ approach to regulating content. By comparison, the EU, and countries like Germany and Australia, have implemented regulations that require platforms to remove harmful content, report criminal activity, and ensure transparency, with evidence suggesting this has reduced both online and offline hate in Germany.[36] Australia also recently passed a social media ban for children under 16, emphasizing the social responsibility that platforms have in protecting young users from online harm.[37] Repealing or reforming Section 230 would compel U.S. platforms to adopt stricter measures for detecting and removing hate speech, as well as geo-blocking content like Holocaust denial that violates laws in other countries. Governments should also enforce clear, consistent community guidelines that define harmful speech, ideally aligning with international frameworks like the UDHR.

To tackle the amplification of hate speech, another recommendation is to regulate the AI and algorithms used by social media platforms. These algorithms prioritize sensational content like hate speech to boost user engagement and maximize profit. The algorithms’ inability to understand linguistic diversity, coded hate speech and contextual nuances also allows hate speech to go undetected.[38] Governments should impose stricter regulations on these algorithms, requiring platforms to increase accountability, improve reporting systems, and quickly remove flagged posts. Transparent practices would also enable advertisers and users to hold platforms accountable, advocate for better protections, or choose platforms that encourage safer, more inclusive content. Moreover, governments should mandate algorithm redesigns that promote inclusive and diverse content over harmful material, which would prevent the spread of hate speech while still protecting free speech.

Regulation alone, however, doesn’t deal with the societal attitudes, like prejudice, discrimination and ignorance, that fuel hate speech. Governments should invest in public awareness and educational campaigns that promote tolerance, empathy and diversity. These campaigns should collaborate with schools, organizations and digital platforms to educate about hate speech’s harm and empower communities to recognize and challenge it constructively. This would strengthen marginalized voices and create opportunities for counterspeech, such as calling out hateful rhetoric by politicians to help counter the normalization of hate. Additionally, governments should provide specialized support systems for victims, including mental health services, legal assistance, and advocacy groups, ensuring victims are heard and supported.

These three recommendations – holding platforms accountable, regulating algorithms, and confronting the root causes of hate speech – offer a comprehensive strategy for combating hate speech that affirms human dignity as paramount. However, hate speech’s global reach means no single country can address this problem in isolation. Its rapid proliferation online demands international cooperation, particularly from the U.S., to establish consistent norms, definitions, and enforcement. Collaborative geopolitical efforts should include binding international treaties and technology standards that promote a unifiedapproach to combating this shared global threat.

Conclusion

In line with António Guterres, it’s clear that hate speech undermines human rights of dignity, security and equality while fueling exclusion, fear and discrimination, making its harm outweigh any value as free speech. While the U.S. prioritizes liberty in dealing with hate speech, other nations prioritize dignity, imposing restrictions to protect human rights. However, hate speech’s prolific rise in recent years shows that not enough is being done. Governments worldwidehave the potential and responsibility to do even more to confront hate speech and its real-world consequences.

To combat the rapid spread of hate speech fueled by the internet and engagement-driven algorithms, governments should enforce stricter content moderation and transparency standards for social media platforms. Tackling the deeper societal prejudices that drive hate speech requires long-term government investment into public education campaigns and community support initiatives. To counter the inconsistencies in legal approaches worldwide, governments need to collaborate internationally to establish shared standards, definitions and norms.Finally, to send a powerful message to the international community, the U.S. should repeal Section 230, criminalize Holocaust denial and justification, and carve out an exception to the First Amendment for hate speech.

Governments hold the power to shape hate speech’sevolution and keep it out of the mainstream permanently. By failing to act, they risk allowing hate speech to continue to threaten human rights and human lives. However, by adopting balanced and comprehensive policies, governments can confront this threat by navigating the line between liberty and dignity and prioritizing the human rights of dignity, security and equality for everyone.

Bibliography

Amnesty International. Myanmar: Facebook’s systems promoted violence against Rohingya. September 29, 2022. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2022/09/myanmar-facebooks-systems-promoted-violence-against-rohingya-meta-owes-reparations-new-report/.

Anti-Defamation League Anti-Bias Education. “The Pyramid of Hate.” ADL, April 14, 2021. https://www.adl.org/resources/tools-and-strategies/pyramid-hate-student-edition.

Anti-Defamation League. Online Hate and Harassment: The American Experience 2023. June 27, 2023.https://www.adl.org/resources/report/online-hate-and-harassment-american-experience-2023?gad_source=1&gclid=CjwKCAiArva5BhBiEiwA-oTnXWUqXqv-EA59L5bqPXFGNnoeEmMrHZiMr_A7x7I1V0fJEmR7-2z_URoCJtkQAvD_BwE&gclsrc=aw.ds.

Carlson, Caitlin R. Hate Speech. MIT Press, 2021.

Cortese, Anthony. Opposing Hate Speech. Praeger, 2006.

Council of Europe. European Convention on Human Rights. November 4, 1950. https://www.echr.coe.int/documents/convention_eng.pdf.

Delgado, Richard. “Words That Wound: A Tort Action for Racial Insults, Epithets, and Name-Calling.” Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review, Vol. 17, 1982. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2000918.

Dixon, Stacy. “Number of Monthly Active Facebook Users Worldwide.” Statista, May 2024. https://www.statista.com/statistics/264810/number-of-monthly-active-facebook-users-worldwide/.

European Citizens’ Panel. “Tackling Hatred in Society.” European Commission, 2024. https://citizens.ec.europa.eu/tackling-hatred-society_en#:~:text=Hateful%20toxicity%20increased%20by%2030,times%20from%202022%20to%202023.

Faheid, Dalia, et al. “Authorities work to find the source of racist texts sent to Black people nationwide.” CNN, November 10, 2024. https://www.cnn.com/2024/11/09/us/racist-texts-black-people-investigation-what-we-know/index.html.

Fish, Stanley. The First. Simon & Schuster, 2019.

Foundation for Individual Rights in Education. Poll: Majority of Americans believe First Amendment goes TOO FAR in the rights it guarantees. August 1, 2024. https://www.thefire.org/news/poll-majority-americans-believe-first-amendment-goes-too-far-rights-it-guarantees.

Foxman, Abraham H. and Christopher Wolf. Viral Hate. Macmillan, 2013.

Frankel, Sheera et al. “On Instagram, 11,696 examples of how hate thrives on social media.” New York Times, October 29, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/29/technology/hate-on-social-media.html.

Futtner, Nora and Natalia Brusco. “Hate Speech is On the Rise.” Geneva International Centre for Justice, March 12, 2024. https://www.gicj.org/gicj-reports/1970-hate-speech-on-the-rise.

Goldsmith, Jack. "Should International Human Rights Law Trump US Domestic Law?" Chicago Journal of International Law: Vol. 1: No. 2, Article 12., 2000. https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cjil/vol1/iss2/12.

Government Accountability Office. Online Extremism. January 12, 2024. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-24-105553.

Government Accountability Office. Online Extremism is a Growing Problem, February 13, 2024. https://www.gao.gov/blog/online-extremism-growing-problem-whats-being-done-about-it.

Herz, Michael and Peter Molnar. The Content and Context of Hate Speech. Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Heyman, Steven J. Free Speech and Human Dignity. Keystone, 2008.

Kemp, Simon. “Digital 2024: Global Overview Report.” DataReportal, January 31, 2024. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2024-global-overview-report#:~:text=More%20than%2066%20percent%20of,since%20the%20start%20of%202023.

Lewis, Anthony. Freedom for the Thought that we Hate. Basic Books, 2007.

MacCarthy, Mark. “What Should Policymakers Do to Encourage Better Platform Content Moderation?” Forbes, May 22, 2019. https://www.forbes.com/sites/washingtonbytes/2019/05/14/what-should-policymakers-do-to-encourage-better-platform-content-moderation/?sh=94c7a831ee49.

Menczer, Filippo. “Elon Musk says relaxing content rules on Twitter will boost free speech.” Nieman Lab, May 9, 2022.https://www.niemanlab.org/2022/05/elon-musk-says-relaxing-content-rules-on-twitter-will-boost-free-speech-but-research-shows-otherwise/.

Mill, John Stuart. On Liberty. Originally published 1859. Reprint, Penguin Classics, 2006.

Milton, John. Areopagitica, 1644. Ed. Edward Arber. Saifer: Philadelphia, 1972.

Müller, Karsren et al. “The effect of content moderation on online and offline hate.” CEPR VoxEU, November 23, 2022. https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/effect-content-moderation-online-and-offline-hate.

Nderitu, Alice W. “Intolerance, Hate Speech Often Very Cause of Wars.” UN Security Council, June 14, 2024, https://press.un.org/en/2024/sc15731.doc.htm.

Pal, Alasdair and Cordelia Hsu, “Australia's under-16 social media ban sparks anger and relief,” Reuters, November 29, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/australian-pm-albanese-says-social-media-firms-now-have-responsibility-protect-2024-11-28/.

Popper, Karl. The Open Society and Its Enemies. Originally published 1945. Reprint, Princeton University Press, 1994.

Post, Robert C. “Racist Speech, Democracy, and the First Amendment,” William and Mary Law Review, 32 ,1991. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol32/iss2/4.

Reid, John W. “Liberty vs. Dignity? A Euro-American Comparison of Two Free Speech Baselines.” Constitutional Discourse, May 15, 2024. https://constitutionaldiscourse.com/liberty-vs-dignity-a-euro-american-comparison-of-two-free-speech-baselines/.

Schweppe, Jennifer and Mark Austin Walters. The Globalization of Hate: Internationalizing Hate Crime? Oxford University Press, 2016.

Sternberg, Robert (Ed.) Perspectives on Hate. American Psychological Association, 2020.

Strossen, Nadine. “Counterspeech in Response to Changing Notions of Free Speech.” American Bar Association, May 2018,

https://www.americanbar.org/groups/crsj/publications/human_rights_magazine_home/the-ongoing-challenge-to-define-free-speech/counterspeech-in-response-to-free-speech/.

Strossen, Nadine. HATE. Oxford University Press, 2018.

Tsesis, Alexander. “Dignity and Speech: The Regulation of Hate Speech in a Democracy.” Wake Forest Law Review 44, May 2009. https://lawecommons.luc.edu/facpubs/40/.

United Nations. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. December 16, 1966. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-civil-and-political-rights.

United Nations. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. December 10, 1948. https://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/.

United NationsArticles:

- “Freedom of speech is not freedom to spread racial hatred on social media,” January 6, 2023. https://www.ohchr.org/en/statements/2023/01/freedom-speech-not-freedom-spread-racial-hatred-social-media-un-experts.

- “Hate Speech versus Freedom of Speech,” May 2019. https://www.un.org/en/hate-speech/understanding-hate-speech/hate-speech-versus-freedom-of-speech.

- “UN Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech,”May 2019. https://www.un.org/en/hate-speech/un-strategy-and-plan-of-action-on-hate-speech.

Waldron, Jeremy. The Harm in Hate Speech. Harvard University Press, 2012.

[1]Dalia Faheid et al., “Authorities work to find the source of racist texts sent to Black people nationwide,” CNN, November 10, 2024, https://www.cnn.com/2024/11/09/us/racist-texts-black-people-investigation-what-we-know/index.html.

[2]Government Accountability Office, Online Extremism is a Growing Problem, February 13, 2024, https://www.gao.gov/blog/online-extremism-growing-problem-whats-being-done-about-it.

[3]United Nations, UN Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech, 2019, https://www.un.org/en/hate-speech/un-strategy-and-plan-of-action-on-hate-speech.

[4]Robert C. Post, “Racist Speech, Democracy, and the First Amendment,” William and Mary Law Review, 32 1991, https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol32/iss2/4, p.273.

[5]Richard Delgado, “Words That Wound: A Tort Action for Racial Insults, Epithets, and Name-Calling,” Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review, Vol. 17, 1982, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2000918, pp.136-40.

[6]Anti-Defamation League Anti-Bias Education, “The Pyramid of Hate,” ADL, April 14, 2021, https://www.adl.org/resources/tools-and-strategies/pyramid-hate-student-edition.

[7]Government Accountability Office, Online Extremism, January 12, 2024, https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-24-105553, p.2.

[8] Nora Futtner and Natalia Brusco, “Hate Speech is On the Rise,” Geneva International Centre for Justice, March 12, 2024, https://www.gicj.org/gicj-reports/1970-hate-speech-on-the-rise.

[9]Alice Wairimu Nderitu, “Intolerance, Hate Speech Often Very Cause of Wars,” UN Security Council, June 14, 2024,https://press.un.org/en/2024/sc15731.doc.htm.

[10]Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Articles 1-3, https://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/.

[11] Robert Sternberg, Perspectives on Hate, American Psychological Association, 2020, p.207.

[12] For example in the U.S., the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (https://www.thefire.org/), and the American Civil Liberties Union (https://www.aclu.org/).

[13]John Milton, Areopagitica, 1644, ed. Edward Arber, Saifer: Philadelphia, 1972, p.74.

[14]Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616, 630 (1919).

[15] Stanley Fish, The First, Simon & Schuster, 2019, pp.47-9.

[16] John Stuart Mill, On Liberty, originally published 1859, reprint Penguin Classics, 2006, p.16.

[17]Alexander Tsesis, “Dignity and Speech: The Regulation of Hate Speech in a Democracy,” Wake Forest Law Review 44, May 2009, https://lawecommons.luc.edu/facpubs/40/, p.521.

[18]Caitlin Ring Carlson, Hate Speech, MIT Press, 2021, pp.46-70.

[19] Anthony Lewis, Freedom for the Thought that we Hate, Basic Books, 2007, pp.157-8.

[20] Karl Popper, The Open Society and Its Enemies, originally published 1945, reprint, Princeton University Press, 1994, p.581.

[21] National Socialist Party of America v. Village of Skokie, 432 U.S. 43 (1977).

[22] American Bar Association surveys from 1991-2008: respondents believing the government should ban hate speech, the lowest agreement 53% (2005) and the highest agreement 78% (1999). In Strossen, 2018. Foundation for Individual Rights in Education survey, 2024: 63-69% Americans believe First Amendment goes too far in the rights it protects, August 1, 2024, https://www.thefire.org/news/poll-majority-americans-believe-first-amendment-goes-too-far-rights-it-guarantees.

[23] Abraham H. Foxman and Christopher Wolf, Viral Hate, Macmillan, 2013, pp.63-7.

[24]Whitney v. California, 274 U.S. 357 (1926).

[25] Arthur Jacobson and Bernhard Schlink, “Hate Speech and Self Restraint,” in The Content and Context of Hate Speech, ed. Michael Herz and Peter Molnar, Cambridge University Press, 2012, pp.220-1.

[26] “Hate Speech versus Freedom of Speech,” United Nations, May 2019, https://www.un.org/en/hate-speech/understanding-hate-speech/hate-speech-versus-freedom-of-speech.

[27] Jack Goldsmith, "Should International Human Rights Law Trump US Domestic Law?," Chicago Journal of International Law: Article 12., 2000, https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cjil/vol1/iss2/12, p.331.

[28]European Citizens’ Panel, “Tackling Hatred in Society,” European Commission, 2024, https://citizens.ec.europa.eu/tackling-hatred-society_en#:~:text=Hateful%20toxicity%20increased%20by%2030,times%20from%202022%20to%202023. Anti-Defamation League, Online Hate and Harassment: The American Experience 2023, June 27, 2023, https://www.adl.org/resources/report/online-hate-and-harassment-american-experience-2023?gad_source=URoCJtkQAvD_BwE&gclsrc=aw.ds.

[29] Simon Kemp, “Digital 2024: Global Overview Report,” DataReportal, January 31, 2024, https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2024-global-overview-since%20the%20start%20of%202023.

[30]Sheera Frankel et al., “On Instagram, 11,696 examples of how hate thrives on social media,” New York Times, October 29, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/29/technology/hate-on-social-media.html. Stacy Dixon, “Number of Monthly Active Facebook Users Worldwide,” Statista, May 2024, https://www.statista.com/statistics/264810/number-of-monthly-active-facebook-users-worldwide/.

[31] “Myanmar: Facebook’s systems promoted violence against Rohingya,” Amnesty International, September 29, 2022, https://www.amnesty.g/en/latest/news/2022/09/myanmar-facebooks-systems-promoted-violence-against-rohingya-meta-owes-reparations-new-report/.

[32] Government Accountability Office, Online Extremism, p.30.

[33]Filippo Menczer, “Elon Musk says relaxing content rules on Twitter will boost free speech,” Nieman Lab, May 9, 2022,https://www.niemanlab.org/2022/05/elon-musk-says-relaxing-content-rules-on-twitter-will-boost-free-speech-but-research-shows-otherwise/.

[34] United Nations, “Freedom of speech is not freedom to spread racial hatred on social media: UN experts,” UN News, January 6, 2023, https://www.ohchr.org/en/statements/2023/01/freedom-speech-not-freedom-spread-racial-hatred-social-media-un-experts.

[35] Carlson, p.159.

[36] EU’s Digital Services Act (2020), Germany’s Network Enforcement Act (2018) and Australia’s Online Safety Act (2021). In Jennifer Schweppe and Mark Austin Walters, The Globalization of Hate: Internationalizing Hate Crime?, Oxford University Press, 2016, p.248. Karsten Müller et al., “The effect of content moderation on online and offline hate,” CEPR VoxEU, November 23, 2022, https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/effect-content-moderation-online-and-offline-hate.

[37] Alasdair Pal and Cordelia Hsu, “Australia's under-16 social media ban sparks anger and relief,” Reuters, November 29, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/australian-pm-albanese-says-social-media-firms-now-have-responsibility-protect-2024-11-28/.

[38]Mark MacCarthy, “What Should Policymakers Do to Encourage Better Platform Content Moderation?” Forbes, May 22, 2019, https://www.forbes.com/sites/washingtonbytes/2019/05/14/what-should-policymakers-do-to-encourage-better-platform-content-moderation/?sh=94c7a831ee49.

Yulisa Ma

11th grade

Miss Porter’s School, Farmington, CT

2nd Prize

When Words Wound: The Case for

Limiting Hate Speech to Protect Human Rights

In societies, freedom of speech is considered the key of democracy, allowing individuals to express their thoughts and ideas without fear of censorship or punishment. Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) reaffirms this principle, stating that “everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression.”[1]

While freedom of speech is a fundamental right, certain circumstances reveal that protecting one person's right to express hate speech can directly violate others' rights, leading to silencing, intimidation, or discrimination. When speech crosses into hate speech—any kind of communication that attacks or uses pejorative or discriminatory language with reference to a person or a group based on identity factors—it poses a real threat to the human rights and freedoms of those targeted.[2]

Hate speech not only perpetuates inequality and discrimination but also undermines the dignity, mental well-being, and security of its targets, with the potential to incite violence, ultimately suppressing their voices and involvement in society. Given these threats to human rights, hate speech should not fall under the protection of free speech; rather, governments should implement restrictive legislation, and promote counterspeech, to effectively combat its harmful impact.

Dignity is the foundation of all human rights as stated in the first sentence of the preamble of UDHR: “Recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world.”[3] In a just society, one’s dignity should be recognized and upheld by other citizens. However, in publicly denying the status of its targets as social equals, hate speech undermines the public assurance that their status is secure. Moreover, public hate reaches out to other hateful persons to affirm and even empower their voices. Instead of assuring dignity, it is replaced with the assurance of hatred.[4]

Hate speech delivers offensive discourse towards a group or an individual based on their inherent characteristics, such as race, religion, gender, or ethnicity.[5] It serves to fuel discrimination by reinforcing harmful stereotypes and creating damaging narratives about the targeted groups, ultimately disseminating these ideas to a wider public. A study of violence in Sweden found that hateful speech spurs negative emotions toward the target community among listeners.[6] Furthermore, research shows that, over time, messages spread by hate speech take root within societal attitudes and norms, creating an environment where discrimination becomes normalized, particularly against minorities who often lack the social power to defend themselves effectively.[7]

The direct effects of language and content of hate speech, along with its societal consequences, have a significant impact on the targeted individual’s mental well-being. Empirical findings suggest that targets of hate speech often experience negative psychological consequences—such as greater anxiety, feelings of fear and insecurity, and sleeping disorders—that can be considered as similar to the effects of traumatizing events.[8] Individuals facing hate speech also experience feelings of ostracization and have often been linked with depression, low self-esteem, and diminished quality of life, resulting in further social alienation.[9]

As hate speech justifies prejudice and normalizes discrimination, it amplifies hostility and influences other members of society to stop viewing the targeted groups as equals. The targeted groups are deprived of dignity, and implanted with a sense of fear and alienation, therefore resulting in the minimizing and suppression of their voices. This creates an environment where minorities feel pressured into silence, fearing further hostility if they speak out. This self-censorship is a direct response to threats or intimidation stemming from hate speech. Research shows that victims of hate speech avoid expressing their views publicly due to feelings of insecurity.[10] They suffer a “chilling effect,” where individuals self-censor as they seek to avoid potential harm.[11] In a 2017 European survey, 75% of those who followed or participated in online debates had encountered instances of abuse and threats, with almost half of these respondents saying that this deterred them from engaging in online discussions.[12] According to a report by Amnesty International, 41% of women who had experienced online abuse or harassment reported feeling physically unsafe afterward. Around 32% of women said they stopped posting content that expressed their opinion on certain issues.[13] This data shows how hate speech silences marginalized voices, hindering certain groups’ right to free expression and participation in society openly.

Hate speech extends beyond personal insult; it creates a social atmosphere that discourages the targeted groups from participating in political and civic life. In public settings, citizens need to have the assurance that their dignity is safeguarded in order to feel free to voice their opinions, pursue their aims, and participate without fear or shame.[14] However, hate speech deprives its victims of the safe psychological conditions needed, therefore, targeted individuals are less likely to engage in democratic activities like attending rallies, or running for office.[15] This leads to a lack of representation of the targeted group, making it less likely that the concerns and needs of these communities would be addressed in policy and governance, further marginalizing them from the democratic process. Hate speech creates a self-reinforcing cycle of exclusion: without the public voice or political ability to advocate for themselves, the societal prejudices against the groups deepen, causing further alienation.

Hate speech threatens the security of individuals and broader communities who share the targeted identity, directly opposing the rights guaranteed in Article 3 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR): “Everyone has the right to life, liberty, and security of person.”[16] While this declaration pertains to many rights, the idea that hate speech threatens the security of individuals could mean their safety of self. Hate speech often serves as a precursor to hate crime. The incendiary language used in hate speech stirs anger, fear, and resentment toward specific groups. By promoting an "us versus them" narrative, hate speech fosters distrust and division within communities, leading to the dehumanization of outgroups who are framed as threats or enemies. This dehumanization, in turn, emboldens audiences to feel justified in targeting those they perceive as outsiders. Research shows that when individuals dehumanize others, they feel less moral responsibility toward them, which increases the likelihood of aggression and violence.[17] This escalation poses a threat not only to the safety of targeted groups but also to society at large.

Public and political speeches given by influential figures or leaders that contain hateful rhetoric often hold significant power to incite violence. Part of the problem is that leaders’ remarks do not fade away after they are given. Incendiary rhetoric from political leaders against minority groups, and other targets is often quickly magnified.[18] Public speech that contains bias and discrimination sets an example for its widespread audience, encouraging them to declare their own prejudices and act on them accordingly, even legitimizing hate-fueled aggression among supporters. This can be seen in the case of former U.S. President Donald Trump and how his frequent use of derogatory comments accompanied with fabricated information in targeting minority groups correlates with the rise of hate crime in the United States. A study based on data collected by the Anti-Defamation League shows that state counties that hosted a Trump campaign rally in 2016 saw hate crime rates more than double compared to similar counties that did not host a rally.[19] FBI data also shows that since Trump’s election, there has been an anomalous spike in hate crimes concentrated in counties where Trump won by larger margins.[20] Donald Trump’s anti-Muslim rhetoric during his 2016 campaign and presidency led to notable upticks in hate crimes against the Muslim community. Researchers at California State University analyzed data across 20 states and reported 196 incidents of hate crimes against Muslims in the US in 2015, a 78 percent increase over the prior year.[21] The trend continued in 2016, anti-Muslim hate crime incidents rose dramatically in 2015 and then increased a further 44 percent in 2016.[22] These statistics demonstrate how public hateful rhetoric could incite violence and threaten the right to security of the targeted group.

While politicians have a large platform, social media has amplified the reach of hate speech by giving the average person more of an opportunity to spout such hate. On social media, users’ experiences online are mediated by algorithms designed to maximize their engagement, not their safety, which often lead to the promotion of extreme content. The digital platforms also allow fringe sites, including peddlers of conspiracies, to reach audiences far broader than their core readership.[23] In the age of social media, inflammatory speech online has been linked with real-world violent acts. In 2018, the Pittsburgh synagogue shooter was an active user on the social media network Gab, known for its minimal content restrictions, which attract extremists banned by mainstream platforms. On Gab, he posted repeatedly about the “great replacement” conspiracy—a belief that Jews were supporting immigration to undermine white populations. This toxic rhetoric, which fueled demographic anxieties about immigration and birth rates, had been echoed previously in the white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017. Believing this conspiracy, he targeted a Jewish congregation, killing 11 worshippers gathered for a refugee-themed service.[24] This example exemplifies how unchecked hate speech on social media can radicalize individuals, resulting in tragic real-world violence.

Given the violence provoked by hate speech and its detrimental effects on society and human rights, countries’ governments should take the responsibility to address this pressing issue. Effective measures must be implemented to combat hate speech. Implementing a full ban on hate speech is complex. A ban on hate speech is often hard to enforce due to its subjective nature and the challenge of defining harmful speech versus protected opinion. However, while a blanket ban may be difficult, establishing legislation can set a clear stance against hate speech, guide societal norms, and give legal instructions on when and how to intervene in the most severe cases.

The European Union (EU) offers an example of this approach, having declared hate-motivated crimes and speech illegal across member countries. Hate speech is defined in EU law as the public incitement to violence or hatred on the basis of certain characteristics, including race, color, religion, descent and national or ethnic origin.[25] The Framework Decision on Racism and Xenophobia (2008) mandates a criminal-law approach to hate speech in public forums such as rallies and speeches across the EU. This approach is intended to ensure that “the same behavior constitutes an offense in all Member States,” and that penalties are “effective, proportionate, and dissuasive” for individuals and organizations involved.[26] By standardizing the definition and penalties, the EU aims to create a unified stance against hate crimes and ensure consistent enforcement across countries.

Countries that address and combat hate speech have shown success in reducing hate speech and crime, illustrating the benefits of such policies. In England and Wales, for example, hate crimes decreased significantly over a 13-year period, falling by 38% from an estimated 307,000 incidents per year to 190,000 incidents annually.[27] In contrast, countries without hate speech regulations, such as the United States, have seen increases in hate crimes. U.S. hate crimes have reached their highest levels in over a decade, with 7,759 incidents reported in 2020 — a 6% increase from 2019, showing a steeper growth than previous years.[28] As demonstrated by the statistics, restrictions on hate speech would help guarantee the right to security of the public.

Since online platforms have played a major role in the dissemination of hate messages and inciting violence in real life, governments need to establish regulations that guide the removal of harmful content and ensure greater accountability for tech companies in monitoring their platforms. Germany enacted the Network Enforcement Act (NetzDG) in 2018, which obligates the covered social media networks to remove content that is “clearly illegal” within 24 hours after receiving a user complaint. If the illegality of the content is not obvious on a surface level, the social network has seven days to investigate and delete it.[29] A recent study has shown that this regulation not only decreased the presence of inflammatory content online but also reduced offline hate crimes by about 1% for every standard deviation increase in far-right social media exposure.[30] Germany’s policy demonstrates the potential of regulatory action, marking a step towards reducing inflammatory online content and therefore curbing related hate crimes.

While Germany’s strategy offers an effective model for reducing the spread of harmful messages, it also highlights the limitations of censorship and bans. Removing hate speech alone does not address deeply ingrained negative sentiments toward minorities that have accumulated over decades, governments should go beyond legislative action and actively speak out against hate speech. A new report from California State University-San Bernardino’s Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism suggests that political rhetoric may play a role in mitigating or fueling hate crimes.[31] The report examined the incidence of hate crimes in the aftermath of two reactions to terrorism from political leaders. First, George W. Bush’s speech following the 9/11 attacks declaring: “Islam is peace” and “the face of terror is not the true faith of Islam,” and second, Trump calling for a ban on Muslims entering the U.S. after the San Bernardino terror attack. The report found a steep rise in hate crimes following Trump’s remarks and a significant drop in hate crimes after Bush’s speech, relative to the number of hate crimes immediately following the initial terror attacks.[32] These examples illustrate that counterspeech from political figures can serve as a powerful tool in combating hate.

By having public officials consistently affirm ideals of human dignity, tolerance, and respect, governments can counter the influence of hateful rhetoric. Counterspeech can be direct, such as by denouncing specific hate incidents, or indirect, through symbolic actions that reinforce inclusive values—like dedicating public monuments to diversity, enacting public holidays that celebrate minority communities, or naming public spaces in honor of civil rights leaders.[33] This counterspeech strategy empowers the state to take an authoritative role in denouncing hate, showing citizens that discriminatory views are unacceptable, and promoting a culture that values inclusivity and actively opposes prejudice.

Hate speech presents a serious threat to individual dignity, equality, and security, posing a threat to fundamental human rights. Through examples of how hateful rhetoric normalizes discrimination, silences voices, and incites violence, it is clear that hate speech has real consequences that go beyond individual expression, impacting communities and societies at large. Legislation and counterspeech are essential tools for mitigating these effects. By taking these measures to address the underlying causes of hate speech and promote a culture of respect, governments can uphold the values of human rights and ensure a safe and inclusive environment for all citizens.

Amnesty International. 2017. “Amnesty Reveals Alarming Impact of Online Abuse against Women.” Amnesty International. November 20. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/press-release/2017/11/amnesty-reveals-alarming-impact-of-online-abuse-against-women/.

Arne Dreißigacker, Philipp Müller, Anna Isenhardt, and Jonas Schemmel. 2024. “Online Hate Speech Victimization: Consequences for Victims’ Feelings of Insecurity.” Crime Science 13 (1). BioMed Central. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40163-024-00204-y.

Buchholz, Katharina. 2021. “Infographic: U.S. Hate Crimes Remain at Heightened Levels.” Statista Infographics. August 31. https://www.statista.com/chart/16100/total-number-of-hate-crime-incidents-recorded-by-the-fbi/.

“Hate Speech Laws in Democratic Countries | Compass Journal.” Compassjournal.org. February 12. https://compassjournal.org/hate-speech-laws-in-democratic-countries/.

Byman, Daniel. 2021. “How Hateful Rhetoric Connects to Real-World Violence.” Brookings. April 9. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/how-hateful-rhetoric-connects-to-real-world-violence/

Council of Europe. n.d. “Hate Speech.” Freedom of Expression. https://www.coe.int/en/web/freedom-expression/hate-speech.

“Countering Cyberhate: More Regulation or More Speech? On JSTOR.” 2024. Jstor.org. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/27880110.

Daalder, Marc. 2021. “The Chilling Effect of Hate Speech.” Newsroom. June 29. https://newsroom.co.nz/2021/06/29/the-chilling-effect-of-hate-speech/.

Durán, Rafael, Karsten Müller, Carlo Schwarz, Leonardo Bursztyn, Fabrizio Germano, Sophie Hatte, SulinRo'ee Levy, et al. 2023. “The Effect of Content Moderation on Online and Offline Hate: Evidence from Germany’s NetzDG *.” https://congress-files.s3.amazonaws.com/2023-07/NetzDG_and_Hate_Crime.pdf.

“EUR-Lex - 32008F0913 - EN - EUR-Lex.” 2013. Europa.eu. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32008F0913.

Foran, Clare. 2016. “Donald Trump, Anti-Muslim Hate Crimes, and Islamophobia.” The Atlantic. The Atlantic. September 22. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2016/09/trump-muslims-islamophobia-hate-crime/500840/.

Gesley, Jenny. 2021. “Germany: Network Enforcement Act Amended to Better Fight Online Hate Speech.” Library of Congress. July 6. https://www.loc.gov/item/global-legal-monitor/2021-07-06/germany-network-enforcement-act-amended-to-better-fight-online-hate-speech/.

“Hate Speech: A Dilemma for Journalists the World Over.” n.d. OpenDemocracy. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/hate-speech-dilemma-for-journalists-world-over/.

Home Office. 2024. “Hate Crime, England and Wales, Year Ending March 2024.” GOV.UK. October 10. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/hate-crime-england-and-wales-year-ending-march-2024/hate-crime-england-and-wales-year-ending-march-2024.

Laub, Zachary. 2019. “Hate Speech on Social Media: Global Comparisons.” Council on Foreign Relations. June 7. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/hate-speech-social-media-global-comparisons.

Lepoutre, Maxime. 2017. “Hate Speech in Public Discourse: A Pessimistic Defense of Counterspeech.” Social Theory and Practice 43 (4): 851–83. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26405309.

Obermaier, Magdalena, and Desirée Schmuck. 2022. “Youths as Targets: Factors of Online Hate Speech Victimization among Adolescents and Young Adults.” Edited by Jessica Vitak. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 27 (4). doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmac012.

Park, Ahran, Minjeong Kim, and Ee-Sun Kim. 2023. “SEM Analysis of Agreement with Regulating Online Hate Speech: Influences of Victimization, Social Harm Assessment, and Regulatory Effectiveness Assessment.” Frontiers in Psychology 14 (December): 1276568. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1276568.

Pitter, Laura. 2017. “Hate Crimes against Muslims in US Continue to Rise in 2016.” Human Rights Watch. May 11. https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/05/11/hate-crimes-against-muslims-us-continue-rise-2016.

Pluta, Agnieszka, Joanna Mazurek, Jakub Wojciechowski, Tomasz Wolak, Wiktor Soral, and MichałBilewicz. 2023. “Exposure to Hate Speech Deteriorates Neurocognitive Mechanisms of the Ability to Understand Others’ Pain.” Scientific Reports 13 (1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-31146-1.

Rushin, Stephen, and Griffin Sims Edwards. 2018. “The Effect of President Trump’s Election on Hate Crimes.” SSRN Electronic Journal, January. doi:https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3102652.

Seglow, Jonathan. 2016. “Hate Speech, Dignity and Self-Respect.” Ethical Theory and Moral Practice 19 (5): 1103–16. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44955460.

“Special Status Report: Hate Crime in the United States.” 2024. Documentcloud.org. https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/3110202-SPECIAL-STATUS-REPORT-v5-9-16-16.html..

Stop Hate UK. 2023. “The Impact of Hate Crime and Discrimination on Mental Health - Guest Blog from PMAC.” Stop Hate UK. August 30. https://www.stophateuk.org/2023/08/30/the-impact-of-hate-crime-and-discrimination-on-mental-health/.

United Nations. 1948. “Universal Declaration of Human Rights.” United Nations. United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights.

“United Nations Strategy and Plan on Actions of Hate Speech.” n.d.

Wachs, Sebastian, Alexander Wettstein, Ludwig Bilz, Norman Krause, Cindy Ballaschk, Julia Kansok-Dusche, and Michelle F. Wright. 2021. “Playing by the Rules? An Investigation of the Relationship between Social Norms and Adolescents’ Hate Speech Perpetration in Schools.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence, December, 088626052110560. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605211056032.

Wahlström, Mattias, Anton Törnberg, and Hans Ekbrand. 2020. “Dynamics of Violent and Dehumanizing Rhetoric in Far-Right Social Media.” New Media & Society 23 (11): 146144482095279. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820952795.

Waldron, Jeremy. 2012. The Harm in Hate Speech. Harvard University Press.

Williamson, Vanessa, and Isabella Gelfand. 2019. “Trump and Racism: What Do the Data Say?” Brookings. August 14. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/trump-and-racism-what-do-the-data-say/.

“World in Paradox: Hate Speech vs. Speech Freedom | Annenberg.” n.d. Www.asc.upenn.edu. https://www.asc.upenn.edu/research/centers/milton-wolf-seminar-media-and-diplomacy/blog/world-paradox-hate-speech-vs-speech-freedom.

[1] United Nations. 1948. “Universal Declaration of Human Rights.” United Nations. United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights.

[2] “United Nations Strategy and Plan on Actions of Hate Speech.”

[3] Ibid.

[4]Lepoutre, Maxime. 2017. “Hate Speech in Public Discourse: A Pessimistic Defense of Counterspeech.” Social Theory and Practice 43 (4): 851–83. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26405309.

[5] Ibid.

[6]Wahlström, Mattias, Anton Törnberg, and Hans Ekbrand. 2020. “Dynamics of Violent and Dehumanizing Rhetoric in Far-Right Social Media.” New Media & Society 23 (11): 146144482095279. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820952795.

[7]Wachs, Sebastian, Alexander Wettstein, Ludwig Bilz, Norman Krause, Cindy Ballaschk, Julia Kansok-Dusche, and Michelle F. Wright. 2021. “Playing by the Rules? An Investigation of the Relationship between Social Norms and Adolescents’ Hate Speech Perpetration in Schools.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence, December, 088626052110560. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605211056032.

[8]Obermaier, Magdalena, and Desirée Schmuck. 2022. “Youths as Targets: Factors of Online Hate Speech Victimization among Adolescents and Young Adults.” Edited by Jessica Vitak. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 27 (4). doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmac012.

[9] Stop Hate UK. 2023. “The Impact of Hate Crime and Discrimination on Mental Health - Guest Blog from PMAC.” Stop Hate UK. August 30. https://www.stophateuk.org/2023/08/30/the-impact-of-hate-crime-and-discrimination-on-mental-health/.

[10] Arne Dreißigacker, Philipp Müller, Anna Isenhardt, and Jonas Schemmel. 2024. “Online Hate Speech Victimization: Consequences for Victims’ Feelings of Insecurity.” Crime Science 13 (1). BioMed Central. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40163-024-00204-y.

[11] Daalder, Marc. 2021. “The Chilling Effect of Hate Speech.” Newsroom. June 29. https://newsroom.co.nz/2021/06/29/the-chilling-effect-of-hate-speech/.

[12] Park, Ahran, Minjeong Kim, and Ee-Sun Kim. 2023. “SEM Analysis of Agreement with Regulating Online Hate Speech: Influences of Victimization, Social Harm Assessment, and Regulatory Effectiveness Assessment.” Frontiers in Psychology 14 (December): 1276568. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1276568.

[13] Amnesty International. 2017. “Amnesty Reveals Alarming Impact of Online Abuse against Women.” Amnesty International. November 20. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/press-release/2017/11/amnesty-reveals-alarming-impact-of-online-abuse-against-women/.

[14] Waldron, Jeremy. 2012. The Harm in Hate Speech. Harvard University Press.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Pluta, Agnieszka, Joanna Mazurek, Jakub Wojciechowski, Tomasz Wolak, Wiktor Soral, and MichałBilewicz.

2023. “Exposure to Hate Speech Deteriorates Neurocognitive Mechanisms of the Ability to Understand Others’

Pain.” Scientific Reports 13 (1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-31146-1.

[18] Daniel, Byman, 2021. “How Hateful Rhetoric Connects to Real-World Violence.” Brookings. April 9. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/how-hateful-rhetoric-connects-to-real-world-violence/.

[19] Williamson, Vanessa, and Isabella Gelfand. 2019. “Trump and Racism: What Does the Data Say?” Brookings. August 14. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/trump-and-racism-what-do-the-data-say/.

[20] Rushin, Stephen, and Griffin Sims Edwards. 2018. “The Effect of President Trump’s Election on Hate Crimes.” SSRN Electronic Journal, January. doi:https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3102652.

[21] Pitter, Laura. 2017. “Hate Crimes against Muslims in US Continue to Rise in 2016.” Human Rights Watch. May 11. https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/05/11/hate-crimes-against-muslims-us-continue-rise-2016.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Laub, Zachary. 2019. “Hate Speech on Social Media: Global Comparisons.” Council on Foreign Relations. June 7. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/hate-speech-social-media-global-comparisons.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Council of Europe. n.d. “Hate Speech.” Freedom of Expression. https://www.coe.int/en/web/freedom-expression/hate-speech.

[26]“ EUR-Lex - 32008F0913 - EN - EUR-Lex.” 2013. Europa.eu. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32008F0913.

[27] Home Office. 2024. “Hate Crime, England and Wales, Year Ending March 2024.” GOV.UK. October 10. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/hate-crime-england-and-wales-year-ending-march-2024/hate-crime-england-and-wales-year-ending-march-2024.

[28] Buchholz, Katharina. 2021. “Infographic: U.S. Hate Crimes Remain at Heightened Levels.” Statista Infographics. August 31. https://www.statista.com/chart/16100/total-number-of-hate-crime-incidents-recorded-by-the-fbi/.

[29]Gesley, Jenny. 2021. “Germany: Network Enforcement Act Amended to Better Fight Online Hate Speech.” Library of Congress. July 6. https://www.loc.gov/item/global-legal-monitor/2021-07-06/germany-network-enforcement-act-amended-to-better-fight-online-hate-speech/.

[30] Durán, Rafael, Karsten Müller, Carlo Schwarz, Leonardo Bursztyn, Fabrizio Germano, Sophie Hatte, SulinRo'ee Levy, et al. 2023. “The Effect of Content Moderation on Online and Offline Hate: Evidence from Germany’s NetzDG *.” https://congress-files.s3.amazonaws.com/2023-07/NetzDG_and_Hate_Crime.pdf.

[31] “Special Status Report: Hate Crime in the United States.” 2024. Documentcloud.org. https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/3110202-SPECIAL-STATUS-REPORT-v5-9-16-16.html.

[32] Foran, Clare. 2016. “Donald Trump, Anti-Muslim Hate Crimes, and Islamophobia.” The Atlantic. The Atlantic. September 22. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2016/09/trump-muslims-islamophobia-hate-crime/500840/.

[33] Ibid.

Joon Kim

10th grade

Stuyvesant High School, New York City, NY

Shared 3rdPrize

Navigating the Line Between

Free Speech and Hate Speech:

Protecting Rights While Promoting Respect

Freedom of expression is a basic human right and one of the cornerstones of democracy. It is recognized in Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which guarantees everyone's right to hold opinions and to express them freely[1]. The formalization of this right in 1948 was a direct response to the atrocities of World War II, during which authoritarian regimes suppressed any signs of dissent, manipulated information, and fueled propaganda with devastating effect. The post-war international community recognized that the protection of freedom of expression was integral to preventing future oppression and facilitating accountability.

Free speech in democratic societies is important because it allows for open debate, encourages dissent, and facilitates the exchange of ideas. It allows citizens to challenge unjust policies and hold leaders accountable, hence contributing to progress in society. However, this freedom is not within limits. While Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights enunciates the universal right to freedom of expression, hate speech indeed poses a serious threat to human rights, social cohesion, and democratic values. The harm caused by hate speech, such as inciting violence, perpetuating discrimination, and marginalizing vulnerable communities, necessitates a balanced response[2]. Governments should address this threat through transparent and proportional legislation, public-private partnerships with social media platforms, and education initiatives, ensuring the protection of free expression while safeguarding individuals and societies from the harmful effects of hate speech.

Defining Hate Speech and Its Threats

Hate speech is typically defined as any form of communication that incites hatred, discrimination, or violence against individuals or groups based on various attributes such as race, religion, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, or disability[3]. While freedom of expression protects the right to hold unpopular or offensive opinions, hate speech goes beyond this by actively undermining the dignity and safety of targeted individuals and communities. Unlike offensive but non-harmful speech, which can cause disagreement or discomfort, hate speech inflicts a real threat by nurturing an atmosphere of hostility, exclusion, and fear. Hate speech is not confined to words; rather, it causes deep social and psychological injury[4]. It sows fear, inculcates prejudice, and entrenches structural discrimination against vulnerable groups. Victims of hate speech often display symptoms of anxiety, depression, and a diminished feeling of belonging in their respective communities. Furthermore, allowing hate speech to go on without intervention normalizes intolerance and justifies discriminatory conduct, which undermines social cohesion, enabling cycles of oppression.

Real-world examples illustrate the devastating consequences of hate speech. In Myanmar, social media platforms like Facebook became a tool for spreading anti-Rohingya propaganda, including derogatory language and direct incitement to violence against the Muslim minority[5]. This uncurbed spread of hate speech fueled widespread discrimination, mass violence, and the forced migration of over 700,000 Rohingya, culminating in what the United Nations described as a "textbook example of ethnic cleansing." Similarly, the 2017 Charlottesville rally in the United States underlined how hate speech can cause social unrest[6]. The white supremacist groups organized a rally replete with rhetoric aimed at racial minorities and marginalized communities that turned violent and killed one of the counter-protesters. This incident highlighted how hated ideologies, through the means of online forums and in-person demonstrations, escalate physical violence and polarize people.

Unchecked hate speech puts at risk not just individual rights but also the social fabric through the polarization of communities and erosion of trust. It builds an "us versus them" mentality that brings about deep social chasms and undermines efforts at building inclusive and just societies. The threat that hate speech poses requires an urgent response in proactive ways, balancing the scale with preserving the principles of free expression.

Freedom of Expression vs. Hate Speech

The tension between free expression and the need to address hate speech creates a difficult legal and ethical balancing act. Most legal systems around the world face this challenge, trying to protect the principle of free expression while protecting individuals and communities from harm. Landmark legal precedents and differing national policies reveal diverse approaches to this intricate issue, shaped by historical, cultural, and philosophical considerations. One significant legal precedent in the United States is the 1969 Brandenburg v. Ohio decision, which established a framework for determining when speech crosses the line from protected expression to harmful incitement. In this case, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the conviction of a Ku Klux Klan leader when it ruled that speech is only restricted if it can be said to be “directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action” and “likely to incite or produce such action[7].” That “imminent lawless action” test set a high threshold for limiting speech, emphasizing that expression has to create a clear and present danger in order for restriction to be justified. While this approach protects robust freedom of speech, critics argue that it may do little to address the more subtle, long-term harms of hate speech, which include fostering discrimination and social division.

The “imminent lawless action” test continues to influence how U.S. courts handle hate speech cases, prioritizing individual liberties unless a direct and immediate threat is evident. However, other nations adopt stricter approaches to balancing free speech and harm prevention. For example, Germany has strict hate speech laws under its Strafgesetzbuch(Criminal Code), particularly Section 130, which criminalizes incitement to hatred, Holocaust denial, and other forms of speech that threaten public order[8]. In 2018, Germany introduced the NetzDG law, requiring social media platforms to remove hate speech within 24 hours or face substantial fines[9]. The policies of Germany are guided by a post-World War II commitment to the prevention of hate-fueled violence and to the adage that history should not be allowed to repeat itself. Similarly, the United Kingdom enforces hate speech restrictions through legislation such as the Public Order Act of 1986 and the Racial and Religious Hatred Act of 2006. These laws forbid speech that intentionally stirs racial or religious hatred, emphasizing protection for societal cohesion. The model followed by the UK brings in the need for safeguards, which protect the marginalized group without stifling open debate. Another insight could be the model of Canada, balancing free expression with protection from harm under Section 319 of its Criminal Code, criminalizing "willful promotion of hatred" against identifiable groups[10]. Furthermore, the Canadian Human Rights Act regulates hate speech in contexts where it targets vulnerable populations, reflecting the country's commitment to maintaining a multicultural and inclusive society[11].

These different approaches reflect a variety of judgments on how governments balance the right to free speech with the need to prevent harm. These legal frameworks are underpinned by philosophical perspectives, which are instructive regarding the ethical considerations of regulating hate speech. John Stuart Mill, in his seminal work On Liberty, espoused the principle of free speech, arguing that open expression fosters the pursuit of truth and individual growth. However, Mill also modified this with the “harm principle,” which states that individual liberty should be curtailed if the liberty causes harm to others[12]. In the context of hate speech, this principle justifies regulation when speech violates the rights and well-being of others. Similarly, John Rawls' theory of “justice as fairness” provides a strong rationale for curbing hate speech. Rawls argued that a just society is one that enacts principles protecting the most vulnerable of its members. His Theory of Justice emphasizes that sometimes, in order to create equity and protect the most vulnerable from harm, some rights will have to be curtailed[13]. In that sense, the regulation of hate speech serves the greater aim of creating a society that is both fair and open to all people to participate in without fear of discrimination or violence.

The Role of Governments in Addressing Hate Speech

The government is pivotal in addressing hate speech through policies and laws that strike a balance between protection for free expression and the prevention of harm. Laws and policies to address hate speech have become major tools in combating its proliferation, especially when it incites violence or enacts systemic discrimination. These need to be informed, nonetheless, by principles of fairness, transparency, and proportionality to prevent overreach and preserve democratic integrity.

Legislation Against Hate Speech

Anti-hate speech laws remain a common response to the threats emanating from harmful rhetoric. Many countries have enacted laws that criminalize hate speech, especially when it comes to inciting violence or hatred against a particular group of people. For instance, the European Union's Framework Decision on Racism and Xenophobia (2008) obliges EU member-states to criminalize speech related to incitement to violence or hatred based on race, religion, or ethnicity[14]. This framework allows different legal systems to work in harmony on the issue of hate speech without necessarily violating basic human rights. Most of the penalties related to these laws are fines and, in worst cases, imprisonment, meant to prevent people from uttering inflammatory remarks.

The Public Order Act of the United Kingdom is one such example: The Act has a provision for penalizing incitement to violence either with a fine or imprisonment, depending on the severity of the offense[15]. In this respect, such penalties are meant to deter any government from allowing hate speech to escalate into acts of violence or social unrest. These measures serve as a deterrent and demonstrate a commitment to protecting vulnerable communities from harm. But enforcement should be done with caution to avoid the suppression of legitimate dissent or unpopular opinion.

Principles to Guide Effective Regulation

To ensure that anti-hate speech measures are just and effective, guiding principles are required from governments, such as transparency, proportionality, and judicial oversight. For there to be transparency, one needs to clearly define what hate speech is and how cases are processed. Clearness will help the community understand the purpose and reach of hate speech laws, avoiding misinterpretation or misapplication. For example, the creation and publication of guidelines related to the regulation of hate speech enable individuals to confidently know how far they can go with lawful expression.

Proportionality means that the punishment should match the severity of the offense. Casual offensive remarks, though potentially hurtful, do not deserve the same treatment as explicit calls for violence. Proportionate measures would keep the playing field fair and avoid over-zealous enforcement that might throttle free expression. Judicial oversight adds an additional safeguard: it provides courts with the opportunity to review cases to ensure hate speech regulations do not contravene constitutional protections or principles of justice. This is an oversight that checks the abuse of power and balances free speech with the prevention of harm.

Challenges and Risks

Aside from their potential benefits, hate speech laws have inherent risks: the possibility of overreach by the government and of unintended consequences. One risk is that such laws might be used to suppress political dissent or opposition. Indeed, in a number of countries, governments have abused anti-hate speech laws to silence critics or clamp down on media freedom. This undermines democracy, turning tools designed to protect vulnerable minorities into instruments of authoritarian repression.

Another challenge is the potential for censorship of controversial but important speech. Discussions about sensitive issues, such as immigration policy or systemic inequalities, might be curtailed if perceived as inflammatory, even when these conversations are essential for societal progress. Overly cautious enforcement of hate speech laws can inadvertently suppress valid, constructive dialogue, depriving societies of diverse perspectives.

Finally, too broad laws on hate speech may well result in a “chilling effect,” whereby individuals avoid stating opinions for fear of the legal consequences[16]. The result of such self-censorship is to stifle public debate and hinder progress by dissuading people from debating contentious issues or challenging entrenched views. Striking a balance between regulating harmful speech and protecting free expression is critical to fostering an open, democratic society.

Collaborative Approaches to Combat Hate Speech

Combating hate speech requires a multi-faceted approach that includes collaboration by governments, private entities, and communities for its sustainability. Public-private partnerships, education, and community support programs play important roles in addressing this complex issue.

Public-Private Partnerships

Governments engage with social media companies in the monitoring and removal of harmful content while protecting free speech. Platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube have enormous influence in shaping public discourse; hence, their involvement is critical. Laws like Germany's NetzDG law, which require the deletion of hate speech content within 24 hours, are a good example of how governments can compel accountability from technology companies[17]. A government and private sector collaboration, with guidelines on identifying and curbing hate speech, will go a long way in reducing its spread online. Transparency in enforcement and opportunities for appeal of content takedowns are important in maintaining public trust and ensuring the protection of legitimate expression.

Media Literacy and Education

Promotion of media literacy and educating the citizens about respectful discourse is important for addressing the roots of hate speech. The programs in schools, workplaces, and online can provide people with the ability to recognize and contest toxic narratives while understanding the power of words. By fostering critical thinking and empathy, media literacy programs empower individuals to engage in constructive dialogue and resist misinformation that fuels hate. These skills can be reflected in curricula developed collaboratively by governments and educational institutions to foster more inclusive societies.

Community Support Initiatives

Community-based programs that foster understanding among different groups are an important response to the harm caused by hate speech. Such programs, including interfaith dialogues, anti-bias workshops, and support networks for targeted communities, help rebuild trust and forge solidarity. These programs help knit the social fabric torn apart by hate speech and encourage social cohesion and mutual respect. To this end, governments can support such initiatives with funding, resources, and platforms for dialogue, ensuring that affected communities feel heard and valued.

Conclusion

Freedom of expression, under Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, is the bedrock on which democratic societies exist, allowing for the free flow of ideas, dissensions, and progress. Yet, hate speech has posed a serious threat to all these values by engendering harm, discrimination, and divisions in society. Finding a balance between protecting free expression and addressing the harms caused by hate-driven rhetoric is complicated but very necessary.

When governments are transparent and respect human rights, they can put in place hate speech controls without weakening the foundation of free expression. Evidence that legal frameworks, public-private partnerships, and education programs do work to mitigate the harm from hate speech while protecting democratic freedoms highlights the fact that such initiatives are possible. Any efforts, however, need to be proportionate, under judicial oversight, and prevent misuse to ensure fairness and accountability. However, the struggle against hate speech is not just for governments or institutions; rather, it requires all individuals to be committed to responsible speech as a way to create an environment of respect and inclusion. By promoting considered and compassionate speech, society can come together to create a safer, more harmonious public sphere in which the rights and dignity of all are respected.

Works Cited

“Brandenburg v. Ohio.” Oyez. Accessed November 29, 2024. https://www.oyez.org/cases/1968/492.

“Canadian Human Rights Act (R.S.C., 1985, c. H-6).” Justice Laws Website, November 25, 2024. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/h-6/.

“Council Framework Decision 2008/913/JHA of 28 November 2008 on Combating Certain Forms and Expressions of Racism and Xenophobia by Means of Criminal Law.” EUR. Accessed November 29, 2024.

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32008F0913.

“Criminal Code (R.S.C., 1985, c. C-46).” Justice Laws Website, November 25, 2024. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/c-46/.

Elliott, Debbie. “The Charlottesville Rally 5 Years Later: ‘It’s What You’re Still Trying to Forget.’” NPR, August 12, 2022. https://www.npr.org/2022/08/12/1116942725/the-charlottesville-rally-5-years-later-its-what-youre-still-trying-to-forget.

“German Criminal Code (Strafgesetzbuch – StGB).” Federal Ministry of Justice. Accessed November 29, 2024. https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/englisch_stgb/englisch_stgb.html.

Gesley, Jenny. “Germany: Network Enforcement Act Amended to Better Fight Online Hate Speech.” The Library of Congress, July 6, 2021. https://www.loc.gov/item/global-legal-monitor/2021-07-06/germany-network-enforcement-act-amended-to-better-fight-online-hate-speech/.